Occurrence of Pruritic Urticarial Papules and Plaques in Multiple Pregnancies: Review and Current Update

1Public Health Consultant, Uttar Pradesh, India

2Shree Guru Gobind Singh Tricentenary Medical College and Research Institute, Gurugram, Haryana, India

3University College of Medical Sciences (University of Delhi), Dilshad Garden, Delhi, India

Author and article information

Cite this as

Khan Z, Sami Z, Shree A, Javed A. Occurrence of Pruritic Urticarial Papules and Plaques in Multiple Pregnancies: Review and Current Update. Adv Women’s Health. 2025;3(1): 001-005. Available from: 10.17352/awh.000003

Copyright License

© 2025 Khan Z, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.Abstract

Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy (PUPPP) present as a benign condition, which is a self- limiting inflammatory reaction that typically affects primigravida within the third trimester of pregnancy. Cases of PUPPP are also seen in the postpartum period. The majority of risk factors are those associated with significant skin stretching, as seen in rapid and excessive weight gain, or multiple pregnancies (such as twins). A preliminary narrative review was conducted to summarize and critically assess the prior literature focusing on the association between PUPPP and multiple gestation. A literature search was carried out in electronic databases using controlled vocabulary. According to current studies, the rapid stretching of the skin is responsible for causing an inflammatory reaction, which causes damage to connective tissue, hence forming urticarial or hive-like lesions. Other risk factors include in-vitro fertilization, hormonal therapy, and a primigravida or nulliparous condition. Moreover, multiple gestations are linked with increased levels of estrogen and progesterone. The lesions are elevated with edematous areas of small papules joining to form bigger plaques. The affected area usually includes the upper and lower abdomen, particularly the area within or next to Striae gravidarum, followed by expansion to proximal limbs, primarily thighs, back, and buttocks. Histopathological findings suggest the presence of perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrates of Eosinophils, mononuclear cells, and skin oedema in the dermis, which is mainly composed of T- helper lymphocytes. Women still often seek treatment for symptomatic relief due to the intense itching. Conservative treatments are suitable to control the manifestations during gestation, and the lesions usually resolve shortly after pregnancy. Symptomatic relief can be provided by antihistamines given orally, emollients, and topical steroids.

Introduction

Multiple pregnancies occur as a result of more than one embryo implanting in the uterus. This happens if multiple ova are released during the menstrual cycle and each egg is fertilised by a sperm. Sometimes, a fertilised egg can spontaneously split into two, causing the formation of identical embryos. Primarily because of the increasing use of in vitro fertilisation (IVF), multiple pregnancies are becoming common. The female body during pregnancy undergoes various changes. These can be metabolic, hormonal, immunological, and vascular [1]. These changes can cause specific skin diseases, presenting with a particular kind of pruritic skin disease unique to pregnancy. Of these, ones that are distinct in pregnancy include pemphigoid gestations, polymorphic eruption of pregnancy, intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, and atopic eruption of pregnancy, and these are collectively grouped under dermatoses [2]. Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy, also known as Pruritic Urticarial Papules and Plaques of Pregnancy (PUPPP), is the most common one among these diseases. It is a benign, self-limiting inflammatory disorder that usually affects primigravida in the third trimester of pregnancy or immediately in the postpartum period [3]. Cases of recurrence are rarely seen in subsequent pregnancies. Proposed theory about the aetiology suggests varying levels of sex hormones in the different trimesters and the body’s immunological response to weight gain and distension of abdominal skin, which is seen at a high frequency in cases of multiple pregnancies and can be a possible trigger factor for the disease [4]. This review aims to assess the available literature to find the correlations between PUPPP and multiple pregnancies. A literature search was carried out in electronic databases using a controlled vocabulary strategy and relevant studies in both medical subject headings (MeSH) and advanced electronic databases, including PubMed and Scopus.

Aetiology

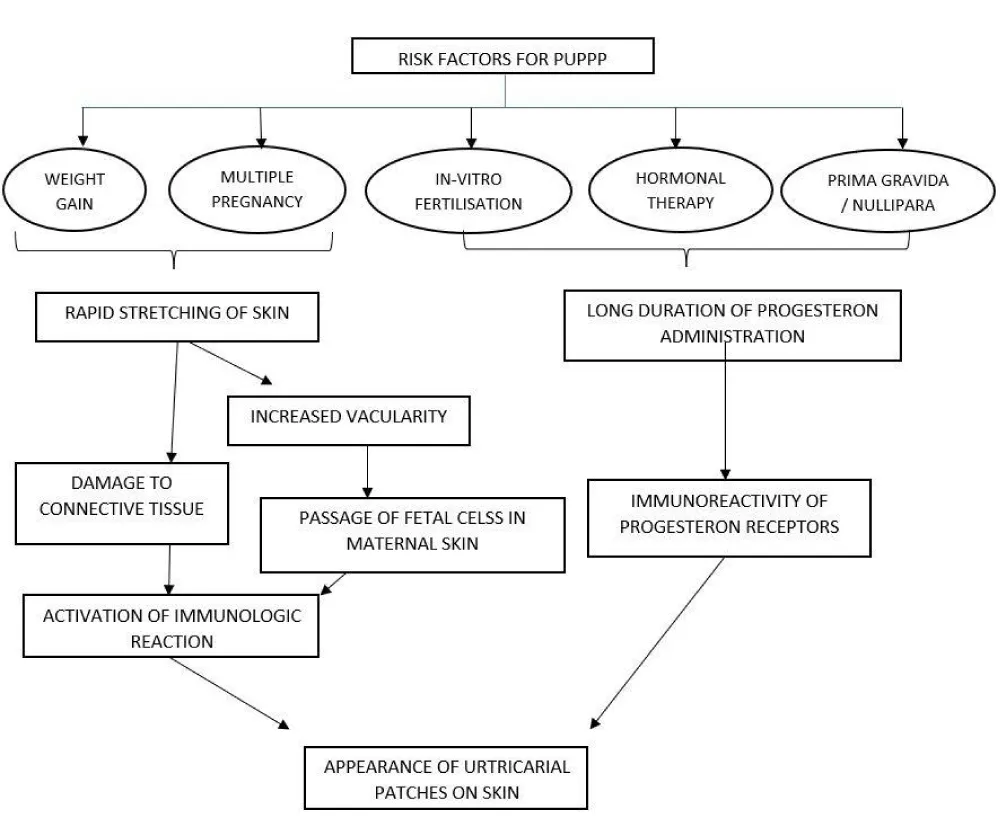

PUPPP is the most commonly found dermatologic condition in pregnant women. It is known to start mostly in the 3rd trimester of pregnancy or at times in the post-partum period. Although there is no specific aetiology reported for the occurrence of PUPPP in the medical literature available, there are certain risk factors that have strong evidence to be associated with its occurrence. The papules and plaques of PUPPP tend to develop in the straie formed in the skin during pregnancy. Thus, the majority of risk factors are all those associated with significant stretching of the skin, as seen in a rapid, excessive increase in weight, multiple pregnancies (twins, etc.). It is thought that the rapid stretching of the skin causes an inflammatory reaction due to damaged connective tissue, resulting in urticarial or hive-like lesions. Other risk factors include in-vitro fertilization, hormonal therapy, and a primigravida or nulliparous condition. The common link in all three is the long duration of progesterone administration. It is the women who never got pregnant before and were under hormonal therapy for infertility that later led to PUPPP in this group. Thus, a persistently high level of progesterone in the blood. Twin pregnancy and immunoreactivity of progesterone receptors in women were found to be at a higher risk [5]. According to Nur D Gungor, et al. the rate of multiple pregnancies was significantly higher (p < 0.001) in in vitro fertilization pregnancies with papules and plaques of pregnancy than in vitro fertilization pregnancies without them. Significantly higher (p < 0.001) duration of progesterone treatment was also found to be associated with in vitro fertilization pregnancies with PUPPP [6]. According to another research, the incidence of PUPPP was found to be 16% - 17% in multiple pregnancies as compared to single pregnancies [7,8] However, there are studies present that testify to no evidence being present to establish any relation between. Laboratory or clinical parameters in cases of PUPPP in pregnant women [9]. Figure 1 summarises the risk factors for PUPPP.

Pathogenesis

The extent of pruritus and the degree of eruption help evaluate the severity of PUPPP [8]. Risk factors for the occurrence of PUPPP include speedy, excessive weight gain or multiple gestational pregnancies such as twins or triplets. The rapid stretching of the skin and abdominal wall distention, with subsequent conversion of nonantigenic molecules to antigenic molecules, causes an inflammatory reaction because of damaged connective tissue, which leads to urticarial or hive-like lesions. Another finding suggests that increased distension of the abdominal wall leads to enhanced vascular permeability, which can cause movement of fetal cells into the mother’s skin, leading to an immunologic reaction, especially in the third trimester [6]. The presence of fetal DNA in the mother’s skin is thought to be a suitable etiological determinant in this disease [10]. Moreover, multiple gestations are linked with increased levels of estrogen and progesterone. Progesterone exacerbates the inflammatory activity at the level of tissues, and the immunoreactivity of progesterone receptors increases, which is detected in the cutaneous lesions of PUPPP. When PUPPP is diagnosed, further lab workup is seemingly redundant due to the positive outcome for both mother and fetus. So far, there is no evidence of Intra-uterine growth retardation and fetal distress [11]. No modifications in the hormonal or immunological profile have been observed. On the other hand, studies using direct immunofluorescence analysis help differentiate PUPPP from Herpes gestationis [12].

Histopathology

Histopathological findings suggest the presence of perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrates of Eosinophils, mononuclear cells, and skin oedema in the dermis, which is mainly composed of T-helper lymphocytes [11]. The appearance of activated T-cells in the dermis shows that they are associated with an increased quantity of dendritic cells and CD1a+ epidermal Langerhans cells in the skin with lesions, as compared to the surrounding unaffected skin. This immune-histologic profile may suggest a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction to the foreign antigen [10,12].

Incidence

PUPPP lesions arise in and around abdominal striae [13]. They last for a short period (averaging about 6 weeks). The age of onset of PUPPP lesions occurs during the gestational period that ranges between 22 and 39 weeks (average of 31.8 weeks). Women in the age group of 25-36 years (averaging about 30 years) show the occurrence of these eruptions. The majority of the patients manifest PUPPP in the last trimester of pregnancy (26-39 weeks), followed by the late half of the second trimester and the immediate postpartum period [14]. Initially, the lesion includes the upper and lower abdomen, particularly the area within or next to Striae gravidarum, followed by expansion to proximal limbs, primarily thighs, back, and buttocks. Initially, it starts itching, then it becomes erythematous and eventually urticarial. In some patients, the lesions can spread to the palms, peripheral limbs (lower extremities), and upper extremities, which may also rarely be affected. Involvement of the periumbilical skin, a mucosal surface, and the face is spared in most cases. This helps us differentiate between Pemphigoid Gestationis, where the cutaneous lesions resemble those of PUPPP, but they originate in the umbilical area. Morphology of the initial lesion is predominantly the stereotypical lesions of urticarial papules and plaques, and sometimes blends into plaques. Some may develop other lesions like papulovesicular rash, eczematous lesions, and target-like lesions. There’s an absence of excoriations on the skin in PUPPP patients, which is a prominent clinical finding, unlike cases of cholestasis of pregnancy that present with frequent excoriations. When PUPPP eruptions resolve, there is an absence of scarring of the skin or post-inflammatory pigmentation [8,13,14] The occurrence of PUPPP in a single pregnancy is calculated to be about one in 200 of total pregnancies (0.5%), and there is an increased likelihood of developing PUPPP in twin and triplet pregnancies, rendering patients with multiple gestations highly susceptible to this disease. Primarily, it occurs in nulliparous or primigravida women [13]. A higher rate of Caesarean section has been observed in PUPPP patients with multiple gestations [15].

Manifestations

PUPPP is known to manifest especially in the third trimester of pregnancy or during the post-partum period as an extreme itchy hive-like rash. The lesions are elevated with edematous areas of small papules joining to form bigger plaques. The rashes may present with a pale halo in lighter-skinned patients. There might be a presence of microvesicles over the lesions in some instances, but there is no excoriation. PUPPP is generally found to appear on the abdomen, spreading to the extremities in a few days. Usually, the palms, soles, and face are spared. According to Iris K. Aronson, et al. clinical and immunopathological observations in 57 patients showed that the PUPPP eruption began on the abdomen in 43 patients. Sixteen of these patients did not have striae. Of those with striae, all but one had onset in or around the striae. In other patients, the initial appearance occurred on the arms in 6, wrists in 2, thighs in 2, legs in 1, feet in 2, and face in 1. The eruption frequently became widespread, involving the abdomen, buttocks, upper and lower extremities, chest, and back. Hands were involved in 17, feet in 11, palms in 6, and soles in 3. In addition, the face was involved in 7 patients. The spectrum of clinical morphological features seen in the reported study are – Type 1 – Urtricarial papules and plaques, Type 2 - erythematous patches that were discrete or confluent and surmounted by tiny (1 to 2 mm) papules or vesicles, or clusters or sheets of 1 to 2 mm erythematous papules, with variable vesicles and excoriations and Type 3 - a combination of features found in type I and type II [5]. Generally, histological findings of PUPPP showed dyskeratosis, spongiosis of the epidermis, oedema of the papillary dermis, and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrations1. Direct immunofluorescence studies are negative [16]. Several past studies have revealed that immunofluorescence staining of lesional biopsy of PUPPP specimens is consistently negative for deposition of complement or immunoglobulins at the dermo-epidermal junction. However, occasionally patients have been described with deposits of C3 or IgM in blood vessel walls or granular deposits of C3 at the DEJ [17-19], linear deposits of IgM at the DEJ [17] and anti-epidermal cell surface IgG antibodies [20]. Though the rash and pruritus typically disappear within 15 days after delivery, even without therapy, women often seek treatment for symptomatic relief due to the intense itching. Table 1 above comprises different types of manifestations of PUPPP.

Treatment

Conservative treatments are suitable to control the manifestations during gestation, and the lesions usually resolve shortly after pregnancy [16]. Symptomatic relief can be provided by antihistamines given orally, emollients, and topical steroids [14]. When used appropriately, topical corticosteroids effectively reduce erythema and pruritus and are thought to be safe during pregnancy. Large cohort studies have not shown an increased risk of congenital abnormalities, but prolonged use of very potent agents may be linked to low birth weight and should therefore be avoided or used sparingly. Cetirizine, loratadine, and diphenhydramine are examples of oral antihistamines that are commonly used to relieve pruritus and have good pregnancy safety profiles. The most frequent adverse effect on mothers, especially with first-generation drugs, is drowsiness [21,22]. Initially, the use of Systemic corticosteroids was more prevalent for the treatment of PUPPP. Now Cyclosporines are preferred, and the use of cyclosporine with infliximab is considered the first-line treatment in PUPPP. As a calcineurin inhibitor, cyclosporine generally does not exhibit consistent teratogenic effects in the trials that are currently available. The estimated risks of major congenital abnormalities were not statistically increased in a conventional meta-analysis of in-utero cyclosporine exposure, despite the broad confidence intervals. When cyclosporine is used for severe pruritic dermatoses of pregnancy, it is typically regarded as acceptable when the benefits outweigh the risks. Close maternal monitoring is emphasised to mitigate known class toxicities like hypertension and nephrotoxicity, as well as obstetric surveillance for foetal growth and preeclampsia [23,24] First-line medications for PUPPP are generally well tolerated; however, therapy should be tailored to each patient’s symptoms, gestational age, and comorbidities. We can also use alternative therapies like retinoids and methotrexate for tenacious postpartum cases in non-breastfeeding mothers [25].

Conclusion

The changes in a female body during a gestational period that can cause skin disorders are broadly grouped under dermatosis. Out of which frequently reported cases are of PUPPP. It’s usually benign and self-limiting. The papules and plaques developing initially within the striae, often occurring during pregnancy, are thought to be the possible pathogenesis of the condition. So far, in the currently available medical literature, no specific aetiology has been proven yet. According to the multifactorial prognosis, rapid, excessive weight gain in multiple gestation pregnancy is a considerable risk factor. As the skin stretches rapidly, inflammatory reactions take place because of the damaged connective tissue, leading to urticarial-like skin lesions. Apart from that, there is also an increase in levels of estrogen and progesterone with immunoreactivity of progesterone receptors in multiple pregnancies. Therefore, secretion of progesterone exacerbates the inflammatory activity at the level of cutaneous lesions of PUPPP, which can easily be detected. Generally, the pruritic papules are first found on the abdomen, stretching out to the extremities over time. The palms, soles, and face are spared mostly. It is important to keep a check on the extent of pruritus and the degree of the eruption, as it helps in the evaluation as well as the severity of PUPPP. The histopathological findings of PUPPP suggest the presence of perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrates of eosinophils, mononuclear cells, and skin oedema in the dermis, which is mainly composed of T- helper lymphocytes. It indicates a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction to the foreign antigen. Hence, timely diagnosis is essential, along with symptomatic management by administration of topical corticosteroids and oral antihistamines. In severe cases, the course of systemic corticosteroids can be required. The complications that may arise due to the disorder are rare but should be prevented as they may lead to maternal-fetal comorbidity.

Declarations

Funding: None. The authors have not received any monetary benefit. However, ISCI helped all the authors by providing research mentors to reviewers and other required support.

Authors’ contributions:

- Zuha Khan: Idea and concept of the manuscript

- Zeba Sami: Data collection and drafting

- Anagha Shree Kapil: Data collection and drafting

- Binish Javed: Drafting and formatting

- Amaan Javed: Corresponding author

References

- Teixeira V, Coutinho I, Gameiro R, Vieira R, Gonçalo M. Specific dermatoses of pregnancy. Acta Med Port. 2013;26:593–600. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24192100/

- Kurien G, Carlson K, Badri T. Dermatoses of Pregnancy. 2024 Jan 11. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430864/

- Sävervall C, Sand FL, Thomsen SF. Dermatological diseases associated with pregnancy: Pemphigoid gestationis, polymorphic eruption of pregnancy, intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, and atopic eruption of pregnancy. Dermatology Research and Practice. 2015;2015. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/979635

- Chouk C, Litaiem N. Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy. 2023. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK539700/

- Aronson IK, Bond S, Fiedler VC, Vomvouras S, Gruber D, Ruiz C. Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy: clinical and immunopathologic observations in 57 patients. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1998;39(6):933–939. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0190-9622(98)70265-8

- Gungor ND, Gurbuz T, Ture T. Prolonged luteal phase support with progesterone may increase papules and plaques of pregnancy frequency in pregnancies through in vitro fertilization. Anais Brasileiros de Dermatologia. 2021;96:171–175. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abd.2020.09.002

- Rudolph CM, Al-Fares S, Vaughan-Jones SA, Müllegger RR, Kerl H, Black MM. Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy: clinicopathology and potential trigger factors in 181 patients. British Journal of Dermatology. 2006;154(1):54–60. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06856.x

- Elling SV, McKenna P, Powell FC. Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy in twin and triplet pregnancies. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 2000;14(5):378–381. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1468-3083.2000.00026.x

- Campbell DM, MacGillivray I. The importance of plasma volume expansion and nutrition in twin pregnancy. Acta Geneticae Medicae et Gemellologiae (Roma). 1984;33(1):19–24. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1017/s0001566000007431

- Ohel I, Levy A, Silberstein T, Holcberg G, Sheiner E. Pregnancy outcome of patients with pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy. Journal of Maternal-Fetal and Neonatal Medicine. 2009;19(5):305–308. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/14767050600590573

- Ohlinger R, Seidlitz A, Volgmann T. Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy (PUPPP): a case report. Zeitschrift für Geburtshilfe und Neonatologie. 2003;207(3):107–109. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2003-40973

- Kroumpouzos G, Cohen LM. Specific dermatoses of pregnancy: an evidence-based systematic review. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2003;188(4):1083–1092. Available from: https://www.ajog.org/article/S0002-9378(02)71459-2/fulltext

- Ahmadi S, Powell FC. Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy: current status. Australasian Journal of Dermatology. 2005;46(2):53–60. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-0960.2005.00160.x

- Ghazeeri G, Kibbi AG, Abbas O. Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy: epidemiological, clinical, and histopathological study of 18 cases from Lebanon. International Journal of Dermatology. 2012;51(9):1047–1053. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.05203.x

- Taylor D, Pappo E, Aronson IK. Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy. Clinics in Dermatology. 2016;34(3):383–391. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clindermatol.2016.02.011

- Matz H, Orion E, Wolf R. Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy: polymorphic eruption of pregnancy (PUPPP). Clinics in Dermatology. 2006;24(2):105–108. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clindermatol.2005.10.010

- Alcalay J, Ingber A, Hazaz B, David M, Sandbank M. Linear IgM dermatosis of pregnancy. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1988;18(2 Pt 2):412–415. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0190-9622(88)70059-6

- High WA, Hoang MP, Miller MD. Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy with unusual and extensive palmoplantar involvement. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2005;105(5 Pt 2):1261–1264. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1097/01.aog.0000159564.69522.f9

- Faber WR, Van Joost TH, Hausman R, Weenink GH. Late prurigo of pregnancy. British Journal of Dermatology. 1982;106(5):511–516. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.1982.tb04552.x

- Trattner A, Ingber A, Sandbank M. Antiepidermal cell surface antibodies in a patient with pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1991;24(2 Pt 1):306–308. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0190-9622(08)80623-8

- Kroumpouzos G, Cohen LM. Specific dermatoses of pregnancy: an evidence-based systematic review. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2003;188(4):1083–1092. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1067/mob.2003.129

- Chi CC, Wang SH, Wojnarowska F, Kirtschig G, Davies E, Bennett C. Safety of topical corticosteroids in pregnancy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015;(10):CD007346. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd007346.pub3

- Oz BB, Hackman R, Einarson T, Koren G. Pregnancy outcome after cyclosporine therapy during pregnancy: a meta-analysis. Transplantation. 2001;71(8):1051–1055. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1097/00007890-200104270-00006

- Paziana K, et al. Ciclosporin use during pregnancy. Drug Safety. 2013;36(5):279–294. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-013-0034-x

- Lehrhoff S, Pomeranz MK. Specific dermatoses of pregnancy and their treatment. Dermatologic Therapy. 2013;26(4):274–284. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/dth.12078

Save to Mendeley

Save to Mendeley