Global Journal of Medical and Clinical Case Reports

Vibrio Vulnificus: New Perspectives of a Strange Skin Infection

1University “Magna Graecia” of Catanzaro, CZ, Italy

2University Hospital “Sant’Andrea” of Roma, RM, Italy

3University of Queensland, Brisbane, UQ, Australia

4University “Sapienza” of Roma, RM, Italy

5University of Parma, Italy

6University of Catalunya, Barcelona, Spain

Author and article information

Cite this as

Tammaro A, Cozza PP, De Marco G, Parisella FR, Cantisani C, Chiarello A, et al. Vibrio Vulnificus: New Perspectives of a Strange Skin Infection. Glob J Medical Clin Case Rep. 2026:13(2):020-022. Available from: 10.17352/gjmccr.000239

Copyright License

© 2026 Tammaro T, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.Abstract

A cA couple celebrating their anniversary in the Dominican Republic encountered a severe infection. The husband suffered from cutaneous symptoms like early erythema, sudden cellulitis, necrosis, severe sepsis, and amputation of the arm. The wife suffered from gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea and vomiting, without skin involvement. The man sustained a finger injury during a SPA session and later swam in a swimming pool; then he punctured his skin while eating oysters at a restaurant going to an exacerbation of the symptoms.

Culture identified Vibrio vulnificus as the cause of the infection, exceptionally attributed to contact with freshwater.

Vibrio vulnificus is a highly virulent bacterium that causes severe gastrointestinal, wound, and septicemic infection in individuals with predisposing conditions. Mortality rate is very high, and early diagnosis and therapies are necessary. Vibrio vulnificus lives in seafood, liver, and seawater.

The case report could represent the first case of contamination in freshwater.

Introduction

Vibrio Vulnificus is a member of the Vibrionaceae family whose pathogenic species include V. parahaemoliticus, V. Cholera and V. vulnificus [1]. Vibrio vulnificus is a highly virulent flagellated halophilic motile gram-negative bacterium that causes severe infections, particularly in individuals with predisposing conditions such as Diabetes Mellitus, Immunosuppression, age above 60 years, Male sex, liver Cirrhosis, Hemochromatosis, malignancies, HIV, and renal disease at the end-stage. The infection typically manifests within 24 hours [2,3]. The bacillus is present worldwide and causes wound infections, primary septicemia, and gastrointestinal infections until death.

The bacterium has a high incidence in summer months and in areas with tropical climates such as South Korea, the USA, Japan, Taiwan, and Mexico. Vibrio vulnificus infections carry a 33% mortality rate in the USA, responsible for 95% of seafood-associated deaths. The primary etiology involves handling or consuming contaminated seafood and seawater exposure with open wounds in marine environments such as rivers, deltas, shorelines, and deeper ocean surfaces [1]. This bacterium is commonly found in oysters, crabs, clams, shrimps, mussels, mullets, and sea bass, and it does not change the appearance, taste, or odor of the food.

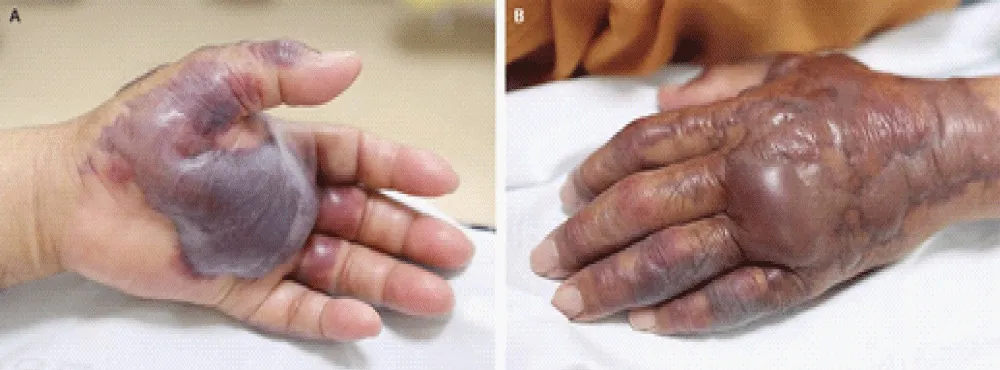

Gastrointestinal symptoms include nausea, fever, diarrhea, and vomiting, and they can rapidly evolve to dramatic septicemia or follow it. Cutaneous symptoms are more rarely registered instead of gastrointestinal ones; it consists on colonizing open wounds evolving with cellulitis, swelling, ulceration, bullae formation, abscesses, and blister formation.

Patients usually enter the emergency department in primary sepsis, due to underestimated symptoms at the start, and they need evaluations using q-SOFA, SIRS, and REMS score at the initial approach.

Biotype 3 has more rarely caused skin and soft tissue infections in freshwater fish farming in Israel. The bacterium thrives in subtropical regions, particularly in waters around 18°C, and men are six times more likely to be affected. Rapid bacterial growth occurs when the host’s transferrin saturation exceeds 70% [1,4].

(Jin Park, M.D., Ph.D., and Chang-Seop Lee, M.D., Ph.D.)Case presentation

A couple celebrating their 50th anniversary in the Dominican Republic encountered a series of typical and atypical events leading to infection. The husband, with obesity, type 2 diabetes, and chronic liver disease from alcohol intake, sustained a finger injury during a SPA session and later swam in the SPA swimming pool (freshwater), developing a mild-moderate local erythema on his skin. Subsequently, he punctured his skin at the same point of the finger injury while shucking oysters at a restaurant, developing more intense erythema and significant soft tissue edema within hours. His wife experienced gastroenteritis symptoms within 18 hours.

In this case, the initial hand lesion was untreated, leading to cellulitis with ecchymosis and hemorrhagic bullae after three days. Despite an occlusive dressing with antiseptic, the cellulitis became necrotic, spreading to the extremity with black and purple eschars, chills, and fever by day five. A maculopapular eruption with necrosis and petechiae on the arms and legs developed. Oral ampicillin was administered, but the condition progressed to abdominal pain and hypotension.

By day six, the patient was admitted to the emergency department in septic shock, necessitating volume infusion and vasoactive agents. Deep debridement for necrotizing fasciitis was required, and the patient was treated with co-trimoxazole and gentamycin. Despite efforts, compartment syndrome led to arm amputation by day eight. The patient developed multi-organ dysfunction, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), rhabdomyolysis, and acute kidney injury (AKI), indicated by elevated D-dimer levels.

Cultures and skin biopsies confirmed the presence of Vibrio vulnificus serotype 1 in wound and blood cultures. Histopathology revealed dermal and subcutaneous inflammation, neutrophilic abscesses, extensive deep dermis destruction, and edematous superficial dermis. Subepidermal bullae contained gram-negative rods, with leukocytoclastic vasculitis and vessel wall necrosis. Fibrin clot formation and extravasated red blood cells were also observed during his recovery [4,5].

Discussion

The first evidence of Vibrio Vulnificus comes from Farmer, et al. [6]. In different case reports, the bacterium came from seafood ingestion and rapidly evolved into septicemia and sepsis within 24 hours. The skin has always been another important target of the infection; in fact, Vibrio Vulnificus penetrates through continuous lesions of the skin, causing rapidly progressive cellulitis, then tissue necrosis and rapid systemic spread. Cutaneous symptoms are related to a high mortality rate, especially in people with predisposing factors, instead of gastrointestinal infection.

In 1981, Bowdre, Poole, and Oliver demonstrated that Vibrio vulnificus (lactose-positive Vibrio) produced extreme hemoconcentration and death within 3 to 6 h after subcutaneous or intraperitoneal injection of viable cells into mice, increasing local vascular permeability, using Evans blue dye. The infection did not require the injection of any toxin, but instead involved direct contact of Vibrio cells with cutaneous and gastrointestinal tissue [7].

Chung et Al also demonstrated that severe forms of the infection, such as necrotizing fasciitis and septicemia, are relatively common among healthy persons, although they may cause fewer deaths than they do among persons with predisposing medical conditions. They focused on the important role of eating seafood such as oysters and undercooked seafood and swimming in tropical locality in which the contact with the bacterium is easier. The infection is more frequent in summer cause of warmer temperatures in seawater related to contact with seafood [8]. The water used in spa pools in the Dominican Republic is typically derived from municipal potable water supplies, groundwater, or, less commonly, local spring or thermally influenced sources (typical fixed residue values between 100-400 mg/L according to the regulations for thermal pools). These waters are originally freshwater and undergo controlled salinization, particularly in systems using salt-based chlorination (electrolysis), resulting in a low to moderate salinity profile. Salinity levels in spa pools are generally well below seawater concentration, but many reach brackish-range values (approximately 5-15 ppt) in international salinized systems: this salinity range overlaps with the optimal environmental conditions for Vibrio vulnificus proliferation. Spa pool temperature is also maintained between 28 and 38 °C in tropical countries; that range is highly permissive for the growth and persistence of Vibrio vulnificus in natural, untreated aquatic environments. Elevated temperature is also associated with enhancing the abundance and virulence of this organism.

Despite potentially favorable temperature and salinity conditions, spa pools are normally subject to continuous water treatment and disinfection with systems such as ozone or ultraviolet radiation. When disinfectant residuals are properly maintained, conditions may be effective in inactivating V. vulnificus and preventing its proliferation. Poor hygiene standards in several tropical countries, combined with the inexperience of poolside staff often employed in pool management, as well as the permissiveness of poolside food consumption (through aperitifs), have certainly contributed to the contamination of freshwater pools, combined with salinity and temperature, making the water an active reservoir for infection, especially if associated with penetration of skin trauma.

Early antibiotic therapy is crucial for treating Vibrio vulnificus infections. Doxycycline 100 mg is the core antibiotic, with fluoroquinolones as alternatives. Intravenous third-generation cephalosporins should be added if sepsis or necrotizing fasciitis is present. Wound care involves non-adherent occlusive or wet-to-dry dressings, with daily inspection and exudate removal. Supportive therapy is vital for sepsis or septic shock [3,9]. In our case, patients was admitted to the emergency department by day six, retarding his treatment of the infection.

Delays in antibiotic administration significantly increase mortality rates, with a 24-hour delay associated with 33% mortality and a 72-hour delay nearly 100%. The incidence of Vibrio vulnificus infections is rising due to better diagnosis, an aging population, and climate change. High-risk individuals should avoid raw seafood and ensure proper wound cleansing after exposure to brackish water or shellfish injuries. Cooking shellfish thoroughly can prevent infection.

In our case rapid development of systemic symptoms can certainly be attributed to the co-morbidity of type 2 Diabetes, in which an elevated blood flow due to cardiac output, and also attributable to elevated heart rate at baseline in diabetic patients (and increased by septicemic conditions), instead of a reduced flow-mediated dilatation [10].

Conclusion

Vibrio vulnificus infection undoubtedly represents one of the major health risks in tropical countries. It results from accidental contact with seawater or the consumption of oysters. Our clinical case certainly represents a novel epidemiological finding: the ingestion of seafood while in contact with swimming pools (which inherently have salinity and temperature characteristics compatible with infection) undoubtedly represents a risk factor for this infection, combined with poor care and disinfection of the pools themselves. A public health intervention of interest could be to limit the consumption of food and beverages in SPA for personal well-being. There is no recent evidence in the literature regarding the onset of infection due to swimming in fresh water. This could represent the first case in literature.

Furthermore, comprehensive patient management, including cardiovascular comorbidities such as diabetes, together with control of blood flow related to diabetes-induced arterial changes (particularly heart rate), is necessary to significantly reduce the spread of infection.

Ethical approval

Reviewed and approved by Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Centro de Investigación Biomedica en Red de Enfermedades Respirorias (CIBERES)

Madrid, Comunidad de Madrid, ES

Ethics statement: The patients in this manuscript have given written informed consent to the publication of their case details

Data availability statement: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- Haftel A, Marietta M, Sharman T. Vibrio vulnificus Infection. 2025 Dec 1. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32119291/

- Strom MS, Paranjpye RN. Epidemiology and pathogenesis of Vibrio vulnificus. Microbes Infect. 2000;2(2):177-88. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/s1286-4579(00)00270-7

- Horseman MA, Surani S. A comprehensive review of Vibrio vulnificus: an important cause of severe sepsis and skin and soft-tissue infection. Int J Infect Dis. 2011;15(3):e157-66. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2010.11.003

- Heng SP, Letchumanan V, Deng CY, Ab Mutalib NS, Khan TM, Chuah LH, et al. Vibrio vulnificus: An Environmental and Clinical Burden. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:997. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2017.00997

- Vibrio vulnificus infection. UpToDate [Internet]. 2024. Available from: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/vibrio-vulnificus-infection

- Farmer JJ 3rd. Vibrio ("Beneckea") vulnificus, the bacterium associated with sepsis, septicaemia, and the sea. Lancet. 1979;2(8148):903. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(79)92715-6

- Bowdre JH, Poole MD, Oliver JD. Edema and hemoconcentration in mice experimentally infected with Vibrio vulnificus. Infect Immun. 1981;32(3):1193-9. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1128/iai.32.3.1193-1199.1981

- Chung PH, Chuang SK, Tsang T, Wai-man L, Yung R, Lo J. Cutaneous injury and Vibrio vulnificus infection. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12(8):1302-3. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1208.051495

- Vibrio vulnificus Expert - Information and Epidemiology. EHA Group [Internet]. Available from: https://www.ehagroup.com/resources/pathogens/vibrio-vulnificus-expert/

- Cutruzzolà A, Parise M, Cozza P, Moraru S, Gnasso A, Irace C. Elevated blood flow in people with type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2024;208:111110. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2024.111110

Save to Mendeley

Save to Mendeley